Kirk Gibson On His Mind, Body and Spirit

By Kyle Koster

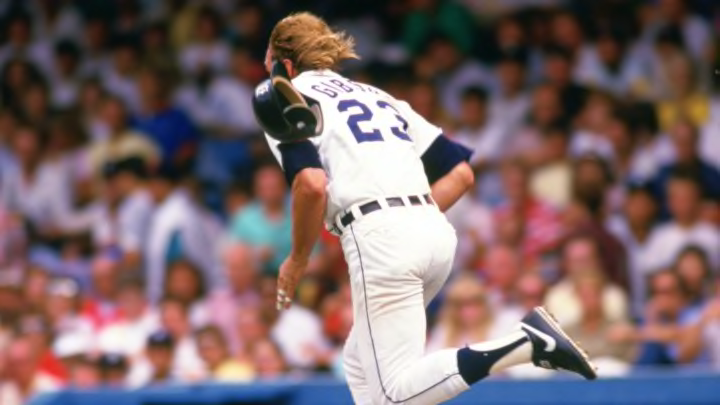

Kirk Gibson was an All-American wide receiver at Michigan State and led the Detroit Tigers to a World Series. In short, he may as well be an athlete created by an algorithm specifically catered to my interests. The Waterford, Mich., native went public with his fight against Parkinson's disease in 2015 and has been using his eponymous foundation as a way to help others in the battle.

The foundation's golf outing runs from Aug. 14-17 and has an option to join virtually. Participants can compete at their course of choice with proceeds going to the charity. Full details and registration can be found here.

Gibson spoke to The Big Lead about giving back, combating an illness in the public eye, and how he learned to harness an ever-active mind.

Kyle Koster: Tell me about your foundation and how the mission has evolved through the years.

Kirk Gibson: I started it in 1996. I wanted to start a foundation to create scholarships for high schoolers. My parents were educators. It was in honor of my mom at Clarkston and in memory of my dad at Waterford Kettering. I sold some of my 1988 memorabilia, did some stuff like that.

To make it a short story, I got diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. We started to get involved after going through this process of not knowing what was wrong with me to finding out and thinking I was going to die to finding out I could live with it. I found out with proper medication and therapy you can have a good life. Parkinson's doesn't really kill you or speed the process up, it just makes life more difficult because you lose a lot of your motor skills and neurons that create dopamine which coordinate your movements and thinking. It's definitely a different life. I was diagnosed in 2015 and my first symptom was in 2007.

My foundation believes in cooperation, collaboration, and teamwork. That's what I was as a player and it is what I am doing with my little part to help people fighting Parkinson's. So much is going toward containing this [corona] virus right now -- as it should -- but I still have it, others have it. Parkinson's is a difficult thing to deal with day in and day out. It's difficult for me and it's difficult for my caregivers so we're trying to create programs that help in anyway that we can.

This would have been our fifth annual golf tournament. The first four went great. We raised and distributed a lot of money for respite programs and research. This year because of the pandemic we thought the best thing was to have the golf be virtual. You can take three of your buddies and roll in the virtual golf classic with us. It takes place Aug. 14-17. You can play against me, try to beat me and whoever beats me by the most wins the prize.

KK: How is your golf game these days?

KG: It was good earlier, it's not very good right now. The putting is still excellent, the chipping is okay. I don't hit a driver because I can't control it. I'm up-and-down but if you challenge me, you might not want to do that. I like to move and compete. Whether it's golf, pool, or ping-pong.

KK: What do you personally get out of having something that helps others?

KG: It feels good. I was very gruff when I first came into baseball from football at Michigan State. In football you put shoulder pads and a helmet on and they blow whistles at you and tell you to dominate and kill this guy across from you. Then practice ends, you take the pads off, take a shower and you're supposed to be some easy-going guy. I had a problem with that. I just wasn't very good at it. You have to find things in your life that give you inner peace. You have to understand what it is to take credit and give credit. Organizing something to help or to help others who have organized something to help is very spiritual. Most people understand what that's like and how it's good for the soul. What I'm learning through my education with the disease, hopefully I can make their journey a little bit easier.

KK: You mention that football mentality, which you brought to baseball. You certainly ran a little hot early in your career but was there a moment during it when you thought about a future in either managing or broadcasting?

KG: Never. I played and then I had a guy at Fox Sports ask me what I thought about doing some television in the late 1990s. I went in and did a little highlight tape and they said I'd be good at it. Then Alan Trammell got a managing job and asked if I wanted to be his bench coach so I went into that. We got fired there. My buddy Bob Melvin asked if I wanted to coach down in Arizona and later I became a manager. Then I got exterminated of that, came back home and Fox said they had a place for me.

You can only plan so much of your journey through life. Some things and opportunities come your way and you run with them and you like them. Other things you run with them and quit them.

I remember I was a free agent when the Dodgers called. I grew up Waterford, went to college at Michigan State, I played for the Tigers,. I did everything in Michigan -- camping, snowmobiling, horseback riding, hiking. I remember thinking, man, LA. We went out there one time for a football game against USC. I just thought that wasn't our style. But ultimately we thought it'd be a three-year commitment, the culture was going to be different, and it was a chance to go with a different team. We went with it and and it changed my life. We won the World Series. I hit the home run. Met great people.

It's like when I went to college. One day we were standing there and the coach said okay, everyone needs to get a roommate. I picked the guy next to me who was from Warren, Ohio. I thought man I thought everyone did things the way we did in Waterford, Michigan. Different cultures and ways to do things, it was a cool experience. I would tell everyone to learn until the day you die. Don't be afraid of the new. There's something interesting you can pick up and pass to others.

KK: It strikes me that you played in front of two of the greatest broadcasters who ever lived in Vin Scully and Ernie Harwell. You're also at the center of one of the greatest calls ever with the homer off Eckersley in the 1988 World Series. How soon after that happened were you able to watch how it played out on the broadcast, considering there weren't immediate uploads online back then?

KG: It was pretty quick. Look, I didn't need to watch it. I lived it. It's vivid. To this day, it's vivid. Vin Scully. Jack Buck. Ernie Harwell. I got to work quite a few games with Ernie on TV. Back in 1998 when Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire were doing the home run chase we were on and were supposed to throw it to a McGwire at-bat in St. Louis. We're doing a live open, talking about the Tigers and we hear in our ear:, throw it to St. Louis, McGwire is at bat. Ernie set it up, threw it to St. Louis and we do our smile at the camera.

But the red light never goes off. We stood there for 40 seconds. The smiles got stale. I didn't know what to do. I could feel my face flushing but Ernie never broke his smile. When we came back on the air he said, well, Gibby, there are three or four million people in China who didn't see that. He was so smooth and soothing.

His last public appearance, Alan Trammell and I sat down to have a chat at a little auditorium. Ernie was supposed to moderate it but he was very sick at the time. We told the guys he wasn't going to be there because he wasn't feeling well. We wished him the best. All of the sudden we heard what we thought was a recording welcoming us to Tigers baseball. It was his voice. I happened to look up and saw him walking down the stairs. He sat down, and we all talked. He was going on fumes but he spread his knowledge and wisdom to the end.

KK: What was some of that wisdom?

KG: Ernie Harwell treated me better than he should have. He treated everyone that way. It was a great lesson. Sometimes when I don't treat someone the best I think back to Ernie Harwell and what he would have done.

Like you said, I was gruff. We get humbled in different ways. Some events in life sit deeper. Hopefully you use them to act appropriately and spread a good word for others behind you.

KK: What has it meant to you to have fans reach out and how have they helped support you?

KG: It's great. It feels good. I hope I can make them proud. I'm going to fight hard for them and their families. There's a lot of people who need help with various things. I do know that teamwork is better than no teamwork. And that's why I'm a proponent of collaboration and cooperation.

You ever do a big puzzle and get stuck where you can't find a piece? You look and look and look. Then I walk up and see it right away and put it in. What happens then? You see one and you're on your way again. That's what the teamwork stuff is about. Be there.

You ever heard of the word scotoma? You've been invested in this big puzzle. You just can't see where you need to go. You're blind to it. I see it immediately. Scotoma is like a blind spot in the sense you're looking at a situation so long, you're so wrapped up in it that you can't see the obvious.

I'm trying to help and have some fun along the way. You think about a marathon or the Tour de France, those guys take turns leading and drafting. Even if you're an enemy, you can work together for the good.

KK: What's it like dealing with this illness as a public figure and what opportunities does it present?

KG: The first thing I did was to come out right away. Most people hide it. It's a burden to hide it. I didn't want to hide it because when your arm is shaking or your hand is clutched and you're putting it in a pocket, you're very anxious about it the whole time.

You have to attack it. If people know, they can help you. There's people who want to help you. You can spread awareness to others. In 2010, I was an interim manager with the Diamondbacks and my hand was very shaky. I had a neck surgery and a shoulder surgery. It was terrible but once I got the proper medication and the proper therapies, they helped. I worked on my posture and everything.

I can walk through an airport and people walk by me who have Parkinson's. You can tell. I try to go over and say I think we have something in common, how you doing today? I broach the subject and we talk about it. I try to be a resource for people who are dealing with it. I try to spend time with people on the phone.

You have a choice. It's not ideal. It's a new normal. But you might as well embrace it. Take the wonderful things you have in your life and go with it. Do you have a bucket list?

KK: I don't, but I should.

KG: Well, I do and it's to do all the things that I know are fun. I don't want to go in there blind and have a stinker. Spending time with my friends and family who have been extremely supportive. And you need that support because sometimes Parky wants you to sit in the corner and be depressed but that's not a good option. I can attest to that.

KK: It might be cliched or reductive to ask this but I'm wondering if baseball, a game of failure and perseverance, gave you any tools to help in this fight.

KG: It did help. It's not fun failing and I don't have the ability to do the things I used to, which bothers me because you still expect to do it. It's like baseball, you don't expect to strikeout, you expect to get a home run every time. But you do strikeout and you need to deal with it and come around to believing by the next at-bat and believe it again. And you do that again, and again, and again.

That was one of my strengths as a player, I had good ability. But I failed a lot but I kept my head up. You can fail a thousand times but that one time you don't in a big moment you realize it's worth it and you don't forget that feeling. You imprint it in your head.

I'd write affirmations when something was bothering me. I remember a good time in my life, close my eyes and say my affirmation and remember what it felt like. What's a good time in your life?

KK: Me? Well, I still get out on the weekends and play ball so probably that.

KG: And how does it feel when you do that?

KK: Honestly, it feels like nothing. The stresses of my outside life aren't there.

KG: You shake off the negativity.

KK: Right. I guess I feel weightless.

KG: I dropped two fly balls on Opening Day in the early 80s on a sunny day. The first one hit me in the side of the shoulder and the other one hit me in the head. I didn't like to play right field on a sunny day after that but I had to change it so I wrote an affirmation about how I enjoyed playing right field at Tiger Stadium on a cold April day because the sun would bear down on me and I could feel the warmth. It made the fans' clothing look like a bright, vibrant painting. Can you picture that?

KK: I can. I remember right as the sun hits the field and the rays beating that blue wall.

KG: Then I remember scoring a touchdown against Michigan in football. I think about how it feels. You say the affirmation, you act like it's already happened, and then you imprint it. I can feel it right now. The ball is up in the air. You have to work on it, whether you have Parkinson's or not.

KK: When did you start doing this?

KG: Well, I don't do it all the time because it'd be too exhausting but I get down. I have, throughout my life, I went to Pacific Institute and met with a great guy named Frank Bartenetti. For three hours I dumped everything on him. I was in a bad spot. Right after I got done dumping everything I was wondering what he was going to say and he just said oh, this is going to be easy to fix. I couldn't believe it.

But he said it would be easy if I chose to make it easy. The lesson was that you have a choice to be your own expert. He said it would be easy and I believed him. I didn't even know the guy.

You go to a restaurant and there's 10 people at your table. There will be one who asks for the rest of the table to go first. It comes to them and they ask the waiter if they should have the fish or chicken. They don't know the waiter or if they need to get rid of the fish or whatever. But if the waiter says fish, they'll take the fish. They've made the waiter the expert. The point is that you can be your own expert. Turn it on yourself. That's a weak food analogy but you can do it with everything in life.

KK: This strikes me as pretty forward-thinking for a baseball player. When did this start?

KG: It was 1983. I needed to do it. It was either get your crap together or -- as Sparky Anderson used to say -- be sitting in mama's lap next year. He humbled me in 1983. I had no choice but to go take care of it. I'm pretty mindful and deep and like to organize a lot of stuff.

KK: But that can be a detriment in baseball. I think of another Tiger, Curtis Granderson, who wrote 'don't think, have fun' on the bill of his hat.

KG: You have to know how to use it. If you have a tool belt, you put it on and look at the job. When it calls for a screwdriver you take it out and use it, then put it back. If it calls for a crowbar, you grab that. You have to fill your tool belt up for situations.

KK: So the year after that, you guys won 35 of the first 40 games. Was that the most fun you've had playing baseball?

KG: No. The two most fun times in baseball were the parades after the World Series runs. All that other stuff didn't rate. I wanted the trophy. When I won the MVP in 1988, I had a reception and it was Kirk, Kirk, Kirk, Kirk did this ... I felt bad for my teammates. I did my part but so many others did as well. So I didn't dig that. But when we had that parade it was great. It was a great party and so many more people got to enjoy it.

KK: Does the word legacy mean anything to you? As a cerebral guy, have you spent any time thinking about what yours will be?

KG: My legacy is making sure I take care of the game for everyone to enjoy it. I did the best I could. Some things weren't very good but I'm not going to get bogged down in that. I have my foundation, I try to spread positivity. I'm going to go until I blow. That's always been my philosophy. I'm going to try to have a good time and enjoy myself. I'm going to stay active and keep the adrenaline flowing.